Michal Hrabánek, a student at the Czech Technical University in Prague (CTU), uses a supercomputer to create architectural visualisations. These are a key part of architectural design - they provide an idea of what a building will look like and often shape its construction. To achieve a photorealistic look, computationally demanding methods such as ray tracing can be used.

Michal Hrabánek, a student of the Faculty of Civil Engineering at the CTU (Architecture and Civil Engineering study programme), uses IT4Innovations supercomputers to create photo-realistic architectural visualisations. Thanks to their power, he achieves detailed and high-quality graphics that would be otherwise difficult for conventional hardware to handle. His visualisations are not only part of student projects - they also serve as representative demonstrations of the rendering capabilities of the supercomputers in the IT4Innovations Visualisation and Virtual Reality Lab.

Hrabánek has recently successfully achieved his bachelor's degree and continues his studies in the Architecture and Civil Engineering MSc study programme at the FCE CTU. He has been actively pursuing his career in the industry for three years. He is currently working in the FormaFatal studio, which specialises in interior design. During their studies, for example, he and his colleague Denisa Englicová designed the renovation and completion of the Dejvice Campus as part of a semester-long project. Hrabánek's projects illustrate how cutting-edge computing power can take architectural visualisation to a whole new level. We talked to him about his experience in the following interview.

Can you tell us more about the "Dejvice project"?

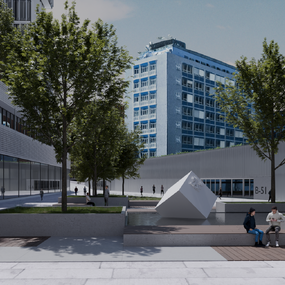

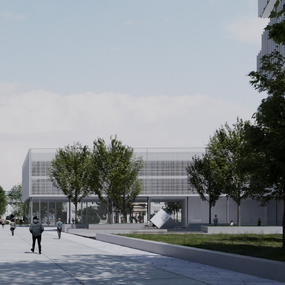

Hrabánek: We focused on the addition of the 4th quadrant of Vítězné náměstí (Kulaťák) in Dejvice, the reconstruction of the laboratories behind the existing Faculty of Electrical Engineering, the design of the new building of the Faculty of Information Technology of the CTU, and the refinement of the 2023 design that won the competition for the renovation of Vítězné náměstí.

It was primarily an urban design project, so we focused on the shapes of the buildings, their facades, exterior areas, and their relationship to the public space. All parts of the assignment were attractive in some way. However, what truly resonated with me was the exterior area of the 4th quadrant on the -1st floor (lower ground floor) with the Metro exit and the design of the three towers of the new FIT building with laboratories.

Our assignment for AMG1 was experimental - instead of a traditional physical model, we had to create a video. Physical models may seem aesthetically pleasing, but video can convey so much more about a project, in my opinion. I see it as a trailer for a film that draws the viewer into the design and shows its story. The ideal would be to combine the architectural presentation board (design poster) with the video and take the physical model as a supplement. The faculty has received our experiment positively, and I hope that making videos will become more and more common in the future.

The major challenge was the time demand. Animation production is a separate discipline, and the faculty does not provide any such classes yet. I dare say I don't think they can fully imagine what it takes to create a quality 3D animation. The original assignment was to create a 10-minute video, which was completely unrealistic - almost like a short film. In the end, we were supposed to submit 5 minutes, but my colleague and I decided to make the video in a way that would appeal to us first and foremost. The result was a 2.5-minute animation, which I think fulfilled its purpose perfectly and was a great success with the jury and visitors to the exhibition.

Animation is not just about "turning the camera". You need to think about the script, the shots, editing, music, and the overall atmosphere. Every second of the video is highly time-consuming, both to create and to render. I couldn't have imagined completing the work without using a supercomputer, especially if the faculty insisted on the original 10 minutes. After all, we are not Pixar to have our in-house render farm.

What made you use a supercomputer for your project?

Hrabánek: Rendering before submitting a project takes a huge amount of time that could be used more efficiently. So, when I learned that I could render externally using a supercomputer, I definitely had to give this option a try. I would like to thank Markéta Faltýnková, thanks to whom I learned about the supercomputer, and the developers of the Bheappe add-on, especially Milan Jaroš, who made it possible to do Blender rendering on a supercomputer.

How exactly have supercomputers helped you in creating visualisations?

Hrabánek: Supercomputers have helped me tremendously, not only with video production but also with visualisation. I work primarily on a MacBook Pro with an M2 Pro chip and use Blender for 3D modelling. The Mac handles the actual model creation very well, even for a large project like this. The problem comes in rendering - while test renders at low resolution take only a few minutes, a full render at high resolution can take tens of minutes to hours.

For comparison, we tested the same scene on my MacBook Pro M2 Pro and an Asus ROG G14 laptop with Intel Core i7 and RTX 4070 graphics card. The result is as follows:

- MacBook Pro M2 Pro → 2 hours

- Asus ROG G14 (RTX 4070) → 30 minutes

Yet even those 30 minutes are challenging if you need several different renders by the next day. And if you find an error, the whole process repeats. That's where the supercomputer, which brings a huge advantage, comes in. After creating a model on my laptop, I make a few test renders and send the file to the supercomputer. The file itself takes the longest to send because of the internet connection, while rendering is a matter of minutes or even seconds. In the same test, the result is as follows:

- Supercomputer→ 5–10 minutes of file upload + 2 minutes of rendering

Compared to a laptop with a dedicated graphics card, I can do fifteen times more renders, plus upload time on a supercomputer and up to sixty times more than on a MacBook.

Another advantage is that I can't do anything else on my computer when I run the render on my machine. But if I send the file to the supercomputer, I can keep working on the 3D model and prepare other scenes.

And we're only talking about the visualisation - a single image. With video, it is an even bigger problem. If we take our campus video at 24 frames per second and 2 minutes 30 seconds long, we get to 3600 frames. Without a powerful rendering engine, this would be utterly unrealistic at regular rendering times.

I should also add that my colleagues used software other than Blender (e.g. Lumion) and rendered the videos on their own devices. Our 2.5-minute video took almost 3 hours to render on a supercomputer, while one colleague processed a 5-minute video, and the render took over 3 days.

Have you encountered any obstacles or challenges when working with a supercomputer?

Hrabánek: The team that developed the Beheppe add-on for Blender did a great job. I did not encounter any significant problems, but one thing could be improved: the user interface. Although I have quite a lot of experience with different software packages, I initially had a bit of trouble navigating the add-on setting needed to set up the project and authenticate the user properly. Moreover, the whole process of creating an account with IT4Innovations was more complicated than I would have expected. I couldn't have done without the help of the experts at IT4Innovations. For comparison, I tried the commercial render GarageFarm.net farm, which I found to be much more intuitive to use and get an account.

Was it difficult to apply for IT4Innovations computational resources? What advice would you give to other students who would also like to use the supercomputer?

Hrabánek: It was challenging for me to write the application because I had no previous experience with a supercomputer and didn't know how many resources to apply for. Applying for something I did not know or use before is hard. Another problem is that many students don't know about this option. Not only do they have no idea that they can apply for computational resources in a grant competition, but many do not even know that they can render, for example, architectural visualisations.

Do you plan to use supercomputers in the future, for example, in further studies or at work??

Hrabánek: I would definitely like to apply for computational resources for my thesis next year. And I would also like to use supercomputers in my work after completing my studies, because they are a huge time saver, which is in short supply in architecture, especially when completing designs. Rendering on an external machine is a great solution in this regard, allowing me to work more efficiently on final visualisations and animations.

However, it will all depend on financial means and the user interface. After completing my studies, it will no longer be a grant but a paid service, so I will have to decide on the most financially and user-friendly option.

We would like to thank Michal Hrabánek very much for the interview and wish him success in his studies and professional life.